http://travelersunited.org/wp-content/uploads/Confucius_Teaching.jpgAnd perhaps equally surprising to many Americans? What did not originate with him are the many proverbs and prognostications attributed to him through fortune cookies distributed in Chinese restaurants nationwide.

Just as an aside, not a single fortune cookie exists in China. And needless to say, those who follow Confucius worldwide celebrate a philosophy that extends well beyond the Golden Rule. A recent visit to Qufu, Confucius’s hometown in Shandong Province, China, immersed me in his life, his teachings and his legacy in a very personal way.

First, a little background. Born Qiu Kong in 551 B.C. and raised by his poor, unwed single mother, Confucius, early on, immersed himself in studies and sought to distinguish himself by mastering the arts usually reserved for those of noble birth: riding chariots, archery, music, mathematics, calligraphy and the rituals of living well. These will become important later on in our story.

Among the principles espoused by Confucius was an emphasis on loyalty, benevolence, wisdom, bravery, simplicity and a basic respect for others that stretched from family relationships to interpersonal ones to those between subjects and rulers. Though they seem like very basic ideas today, during feudal times they were revolutionary.

And throughout his life, he sought to convince local warlords and later emperors (mostly posthumously) that ruling in a just and fair way would reap greater loyalty among their subjects than the totalitarian methods most adopted at the time. He found very few takers. It is one of the many ironies of Confucius’s life that the very emperors whose practices he would have disavowed later came to pay great homage to him.

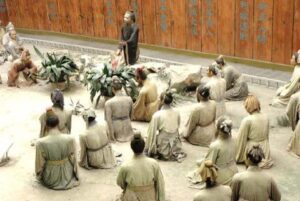

Near the end of his life, he returned to Qufu disillusioned and depressed, where he continued to teach until he died poor and unrecognized at the age of 73. Although his students numbered around 3,000, 72 of them became actual disciples, gathered his teachings into a book called the “Analects,” and continued to spread his word until be eventually became renowned as the “Sage of China.”

First built in 479 B.C., two years after his death, the temple started out as a small abode for his clothes, books, instruments, etc., and was expanded by every dynasty that followed until it reached 466 rooms by the mid-16th century. Every gate, sculpture and stile in some way celebrates his teachings or praises his thinking, whether a commemoration of harmony in relationships or benevolence or respect. Not to be outdone, every emperor in China’s history came to the temple and built a pavilion in his honor — whether that of Confucius or the emperor himself is unclear.

Confucius was an only child, but being the over-achiever that he was, there are now 120,000 descendants with the last name of Kong currently living in Qufu, population 600,000. Not much happens there that doesn’t involve a living relative. And historically, his relatives — or more specifically, the oldest male descendant of each generation — lived a life of ease that far surpassed that enjoyed by Confucius.

The Kong Family Mansion was originally built during the Song Dynasty over 1,000 years ago and was first occupied by the oldest direct male descendant of the 46th generation. Displays throughout the mansion, which served as home for the Kong family for over 800 years, are reminiscent of his teachings: one illustrates his views on dispensing justice, emphasizing rehabilitation over punishment; others display symbols of peace and happiness or warn against greed or disobeying laws.

One of my favorite rooms is the reception hall in which the 77th descendant, the last to live there, got married in 1937. Chiang Kai-Shek was supposed to host the festivities but unfortunately was arrested enroute by one of his opposing generals. One of the visible wedding presents is a sofa given the couple by American diplomat George Marshall, whose name later became synonymous with the post-WW II recovery plan. How fitting that men of political influence continued to honor Confucius throughout the centuries.

In addition to the historically accurate representations of Confucius’s life — and death — Six Arts City, an educational theme park, has been created to replicate the experience of Confucius teachings. Each art that Confucius mastered in his early years has its own exhibit area: archery, music, charioteering, calligraphy, ritual and mathematics. And although I felt it strange to have the high-minded philosophy of Confucius reduced to a theme park ride, still it is well-done for what it is.

And as for those ubiquitous fortune cookies in America? Would Confucius be insulted by them? “Well,” surmised Kong, “although they may not be an accurate reflection of Confucianism, they are still a way to let people know about him as a dispenser of wisdom — even if not originally in the form of fortune cookie quotes.”

For more information about Qufu and other parts of Shandong Province, visit travelshandong.com or email Maggie Zhang at [email protected].

Fyllis Hockman is a multi-award-winning travel journalist who has been traveling and writing for over 30 years — and is still as eager for the next trip as she was for the first. Her articles appear in newspapers across the country and websites across the internet. When not traveling, she is almost as happy watching plays or movies, working out and sitting on a barstool next to her travel-writing husband.